Rethinking Cancer Treatment When Less Medicine Starts Doing More

Rethinking Cancer Treatment When Less Medicine Starts Doing More

For decades, the logic behind cancer treatment has leaned in one direction. Stronger drugs, higher doses, more aggressive protocols. The assumption felt intuitive. If a disease is dangerous, the response should be even stronger. Many oncologists were trained within that framework, and for good reason, because earlier generations of therapies often required that kind of intensity to make any measurable difference.

Yet medicine has a way of humbling its own assumptions. Every few years, a study appears that quietly suggests the body does not always respond the way we expect. Instead of more treatment producing better outcomes, sometimes the opposite happens. That idea might sound counterintuitive at first, but modern immunotherapy is beginning to reveal exactly that pattern.

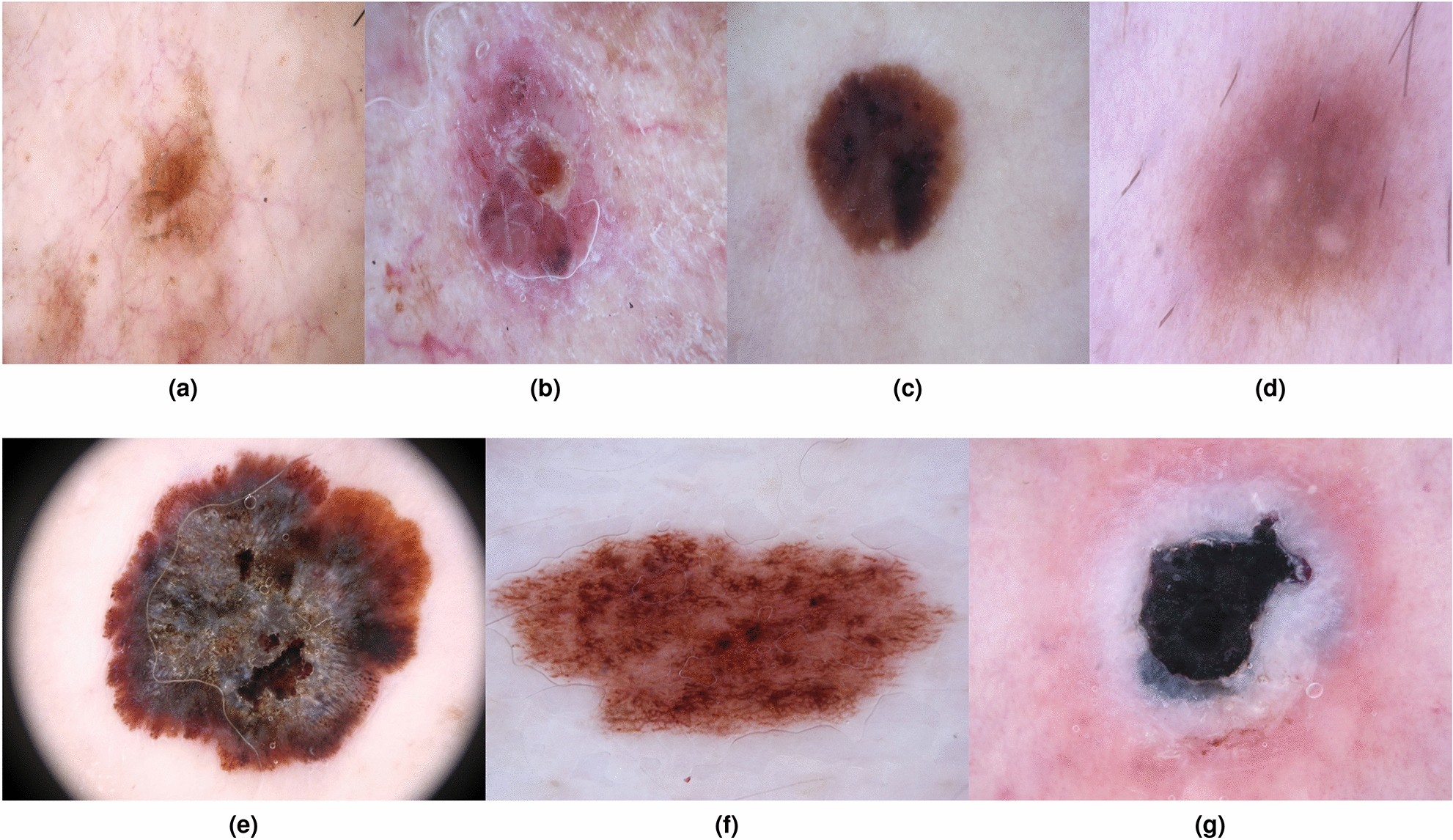

A recent investigation from Karolinska Institutet explored something surprisingly simple. What happens if one of the key drugs used in advanced melanoma therapy is given at a lower dose. The researchers were not trying to reinvent cancer care overnight. They were responding to a practical problem that clinicians see every day, which is severe side effects that force patients to stop treatment earlier than planned.

What they found was unexpected, and frankly a little striking.

When Strong Treatments Become Too Strong

}

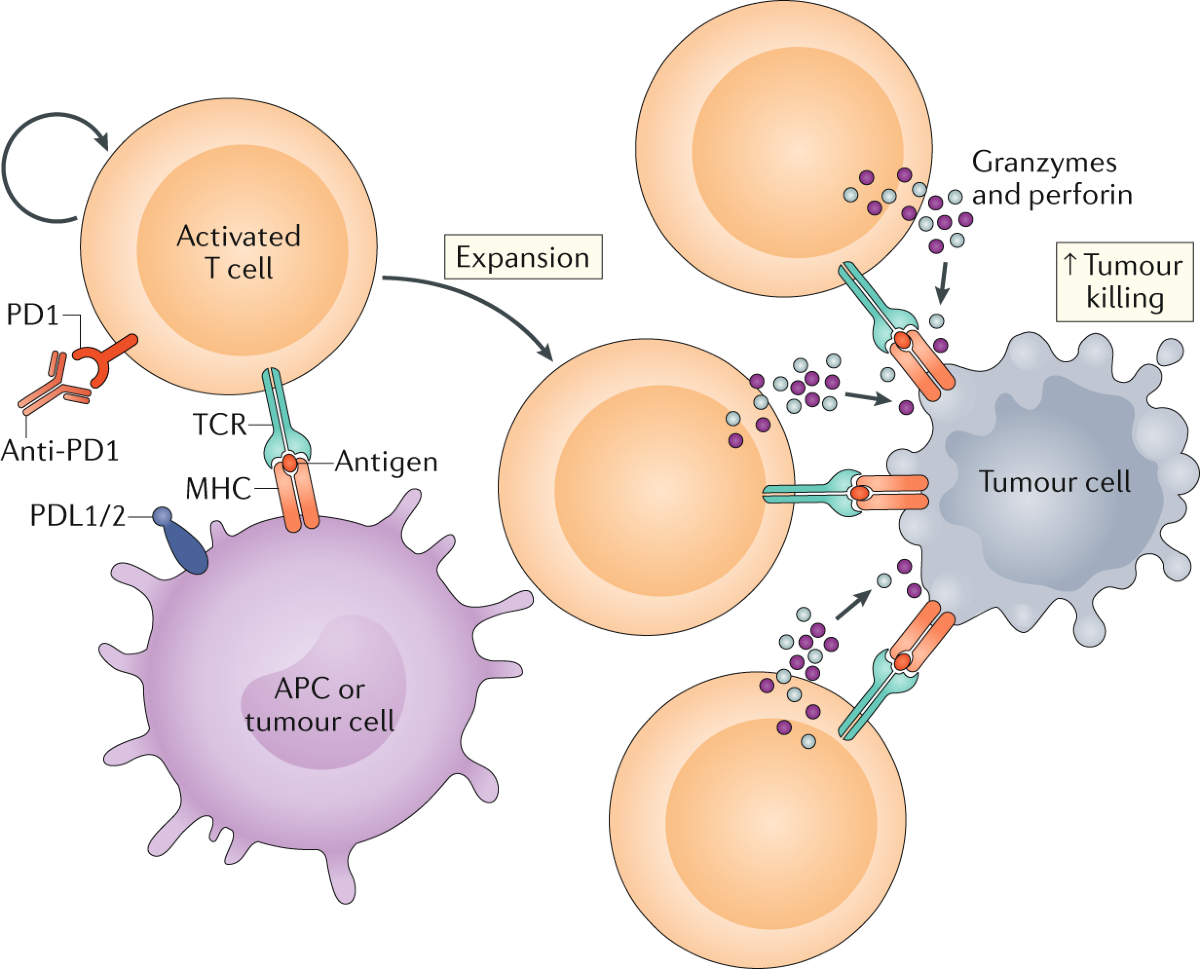

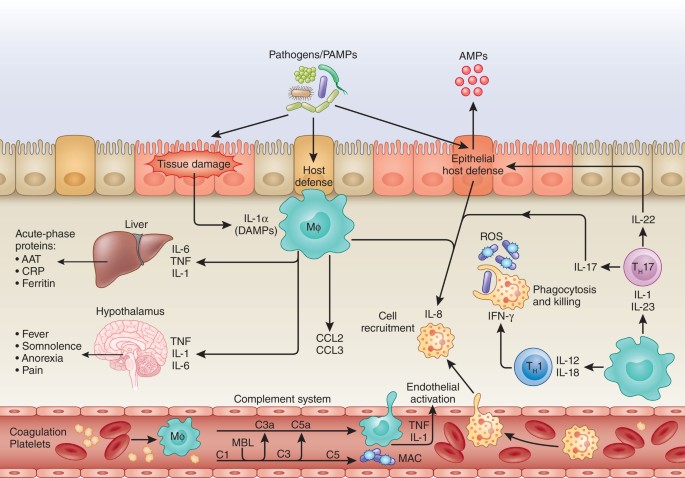

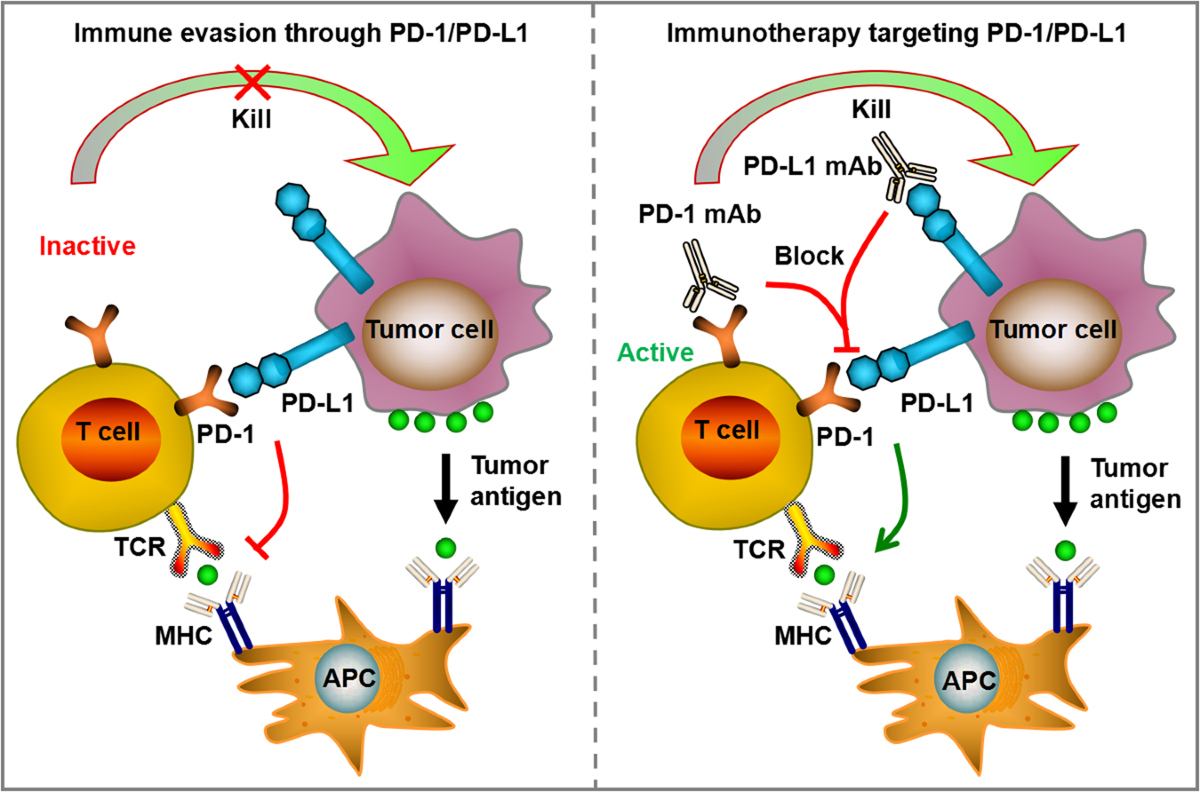

Immunotherapy changed the landscape of oncology in ways that still feel relatively recent. Instead of attacking tumors directly like traditional chemotherapy, these drugs stimulate the immune system so that the body recognizes cancer cells as threats. In theory, that approach sounds elegant. In practice, it can be unpredictable.

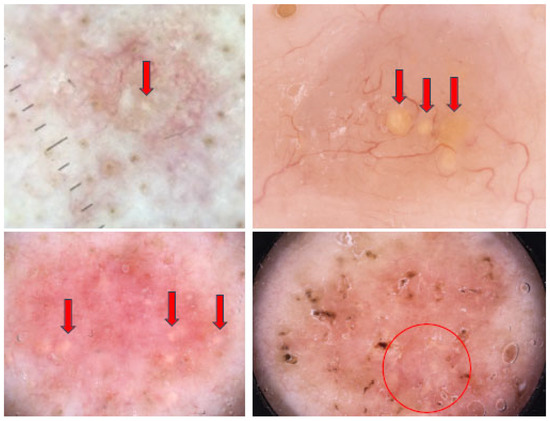

The immune system is powerful, but it is also delicate. When overstimulated, it does not always distinguish between cancer tissue and healthy organs. Patients sometimes develop inflammation in the lungs, liver, skin, or digestive system. Some reactions resolve with treatment. Others become chronic.

Doctors began noticing a pattern. Many patients were responding to immunotherapy early in their treatment cycle, but the side effects escalated before the therapy could reach its full potential.

This raised a quiet but important question. Could the treatment itself be pushing too hard.

The Swedish Approach That Sparked Curiosity

}

Clinicians in Sweden operate within a healthcare structure that sometimes allows more flexibility in dose adjustments compared with systems where insurance rules are tightly standardized. That flexibility opened the door for experimentation, though not in a reckless sense. Physicians were simply trying to make treatments more tolerable.

One of the drugs used in combination immunotherapy for advanced melanoma is known for producing particularly strong immune reactions. It also happens to be the most expensive component of the regimen. Reducing its dose seemed logical from both a safety and cost perspective.

Gradually, oncologists began applying a modified dosing strategy to selected patients. At first, it was a practical adjustment rather than a research hypothesis. However, over time, clinicians noticed something that did not quite fit expectations.

Some patients appeared to be doing better.

That observation eventually motivated a deeper analysis.

Looking Closer at the Data

![]()

}

Researchers reviewed outcomes from nearly four hundred individuals diagnosed with advanced melanoma that could not be removed surgically. These were serious cases where treatment options were already limited.

Two groups naturally emerged from clinical practice. One group received the conventional dosing approach. The other received a reduced dose of one immunotherapy drug while maintaining the rest of the treatment structure.

At first glance, the differences looked modest. Then the survival curves began to separate more clearly.

Patients receiving the lower dose showed higher response rates. Nearly half experienced measurable tumor reduction, compared with a smaller proportion in the traditional dose group. That alone would have been interesting. What made the results more compelling was the duration of disease control.

The average time before the cancer worsened was significantly longer in the reduced dose group. Even more striking was the difference in overall survival.

These patients were living substantially longer.

Why Fewer Side Effects Might Lead to Better Outcomes

}

At first, it might seem odd that a weaker dose could produce stronger results. However, the explanation begins to make sense when viewed through the lens of treatment continuity.

Severe immune reactions often force therapy interruptions. Steroid medications may be required to calm inflammation. In extreme cases, immunotherapy must stop completely. When that happens, the immune system loses sustained stimulation against the tumor.

Lower dosing appears to reduce the frequency of these complications. Patients remain on treatment longer. The immune system receives steady rather than overwhelming activation.

There is also a broader biological possibility that researchers are still exploring. Extremely high immune activation may sometimes trigger regulatory pathways that dampen the response. The immune system, after all, contains built in balancing mechanisms.

Too much stimulation could paradoxically reduce effectiveness.

The idea remains under investigation, yet it illustrates how complex immune biology can be.

Understanding the Limits of the Study

}

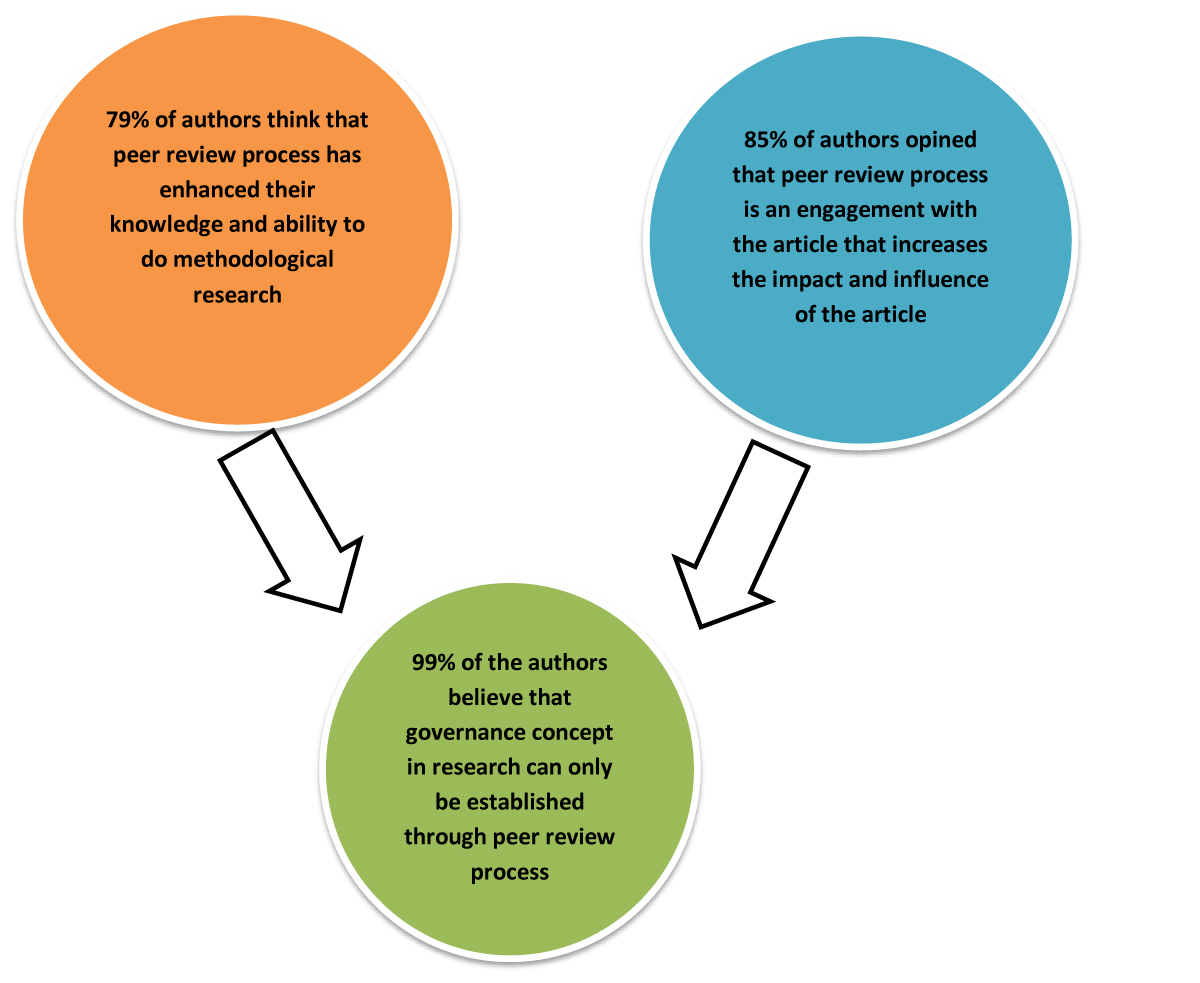

The findings were published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, which adds scientific credibility. Even so, the researchers were careful not to overstate their conclusions.

The analysis was retrospective, meaning it examined existing patient data rather than assigning treatments randomly in a controlled trial. That distinction matters. Observational results can reveal patterns, but they cannot fully prove causation.

Different patient characteristics might have influenced outcomes. Age, tumor biology, or overall health differences sometimes shift survival results in ways that are difficult to isolate completely.

Statistical adjustments help, yet they cannot eliminate all uncertainty.

In other words, the results are promising, though not definitive.

Collaboration Behind the Research

}

The project was conducted in collaboration with Sahlgrenska University Hospital, one of the leading cancer treatment centers in Scandinavia. Large collaborative environments like this are increasingly essential because modern oncology generates enormous datasets.

Immunotherapy research especially requires long term follow up. Tumor responses may unfold gradually over months or years. Some patients experience delayed improvement after initial uncertainty, which would have seemed unusual in earlier eras of cancer treatment.

Funding support came from regional research organizations and cancer foundations, reflecting a growing international effort to refine immunotherapy rather than simply expand it.

This shift toward optimization is becoming more common across medicine.

A Broader Pattern Emerging in Oncology

}

The idea that less treatment can sometimes be more effective is not entirely new. Radiation therapy has already moved in that direction for certain cancers, where carefully targeted lower exposure strategies reduce long term damage.

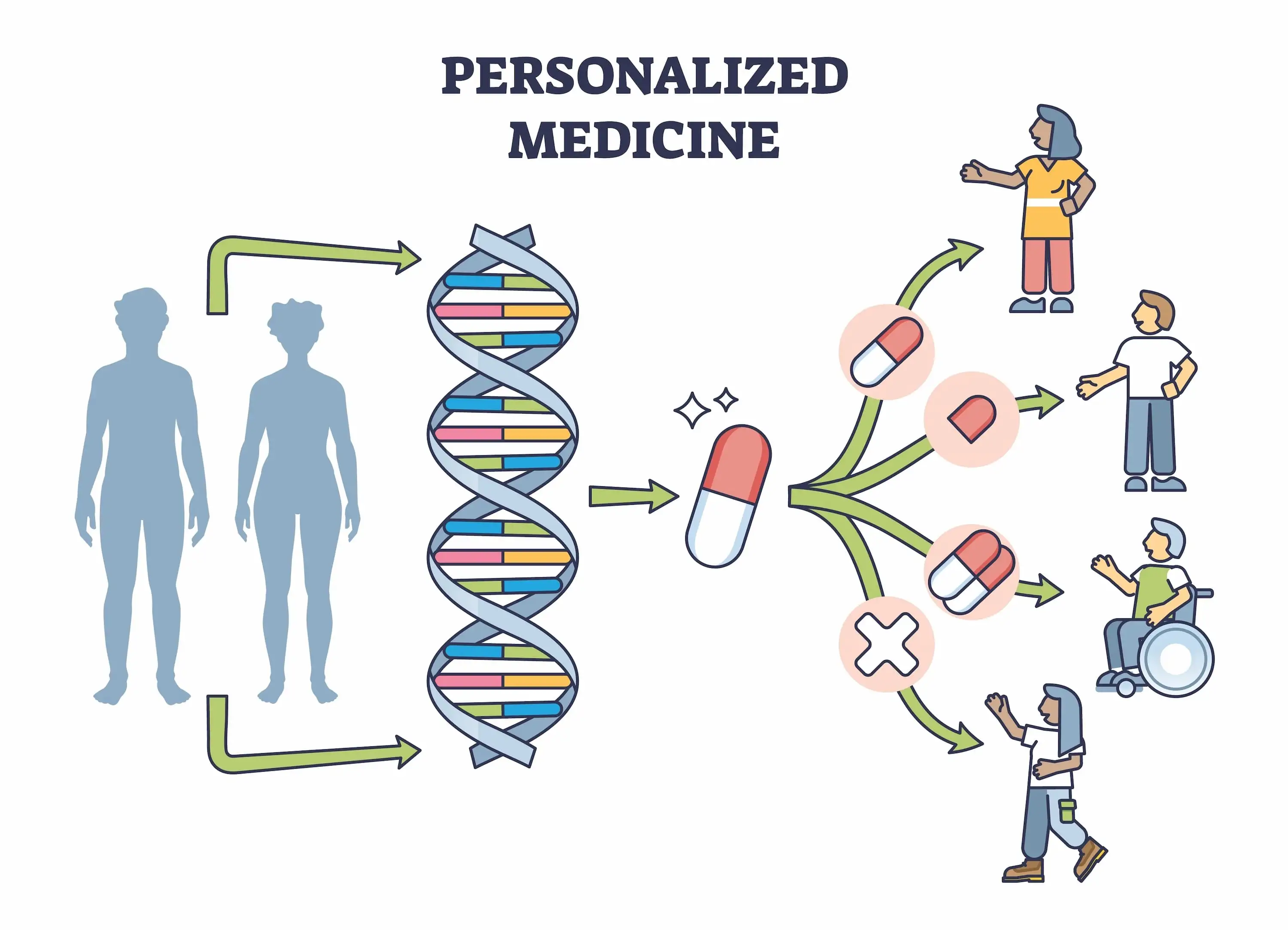

Precision medicine is gradually reshaping how clinicians think about dosing. Instead of one universal protocol, treatments are increasingly adjusted according to biological response.

Some oncologists compare it to tuning a musical instrument. Tightening the string too much does not improve the sound. It simply causes distortion or breakage.

The immune system behaves similarly. It needs stimulation, but not chaos.

Moreover, patients are not identical. Genetic background, microbiome composition, lifestyle factors, and tumor mutations all influence how the immune system reacts.

The future of cancer treatment may depend less on stronger therapies and more on smarter calibration.

The Patient Perspective That Often Gets Overlooked

}

Clinical statistics can feel abstract until they intersect with real lives. Side effects are not just percentages in a table. They translate into fatigue, hospital visits, interrupted routines, and difficult decisions.

Consider a patient who begins immunotherapy while still working part time. Severe immune related complications may require extended steroid therapy, which can disrupt sleep patterns and energy levels. Suddenly, maintaining daily structure becomes challenging.

If a lower dose allows that same patient to continue treatment without those complications, the difference extends beyond survival curves. It affects quality of life in tangible ways.

Many oncologists are increasingly aware of this dimension. Survival remains the primary goal, yet how patients live during treatment matters as well.

What Happens Next

}

The logical next step is a controlled clinical trial designed specifically to compare dosing strategies. Such trials require time, funding, and international coordination.

Regulatory agencies will also need strong evidence before adjusting official treatment guidelines. Oncology protocols change carefully because the stakes are high.

Still, momentum appears to be building. Researchers across multiple countries are now exploring dose optimization strategies for immunotherapy combinations.

The broader message is subtle but important. Medical progress does not always come from discovering entirely new drugs. Sometimes it comes from learning how to use existing therapies more intelligently.

A Shift in How We Think About Strength in Medicine

There is something philosophically interesting about these findings. For many years, strength in cancer treatment meant intensity. Larger doses suggested greater power against disease.

Now the definition is evolving. Strength may instead mean balance.

Immunotherapy works by guiding the immune system rather than overwhelming it. That distinction changes how success is measured. Instead of asking how much drug can be tolerated, clinicians are beginning to ask how much is actually necessary.

That question sounds simple, though answering it requires deep biological understanding.

Research from Karolinska Institutet contributes to this evolving perspective. The results do not close the conversation. If anything, they open new directions.

Medicine often advances through these moments of reconsideration. A long held assumption becomes slightly uncertain. Data introduces nuance. Clinicians adapt.

And somewhere within that process, patients benefit.

The idea that a lower dose could improve survival while reducing complications might once have sounded improbable. Now it feels plausible, supported by evidence yet still inviting further exploration.

Progress rarely arrives all at once. More often, it appears in careful adjustments that slowly reshape how treatment works in the real world.

Open Your Mind !!!

Source: ScienceDaily

Comments

Post a Comment