Exercise and Osteoarthritis Rethinking a Familiar Recommendation

Exercise and Osteoarthritis Rethinking a Familiar Recommendation

For years, people diagnosed with osteoarthritis have heard the same advice almost immediately after leaving the clinic. Move more. Strengthen the muscles. Stay active. The message is repeated so often that it begins to sound less like medical guidance and more like a universal rule.

And to be fair, the logic behind it makes sense. If joints become stiff and painful, improving mobility and muscle support should help stabilize movement. Many patients genuinely feel some relief when they begin gentle routines such as walking, light resistance training, or guided physiotherapy.

However, a large new analysis suggests the situation may be more complicated than the familiar recommendation implies. Researchers reviewing decades of clinical evidence found that the real impact of exercise on osteoarthritis pain and function may be smaller and shorter lived than many people expect.

The findings, published through BMJ Group in the journal RMD Open, do not argue that exercise is useless. Instead, they gently challenge the idea that it works equally well for everyone.

That distinction matters more than it first appears.

The Routine Advice Almost Every Patient Hears

Imagine a typical scenario. Someone begins noticing knee discomfort when climbing stairs. At first it feels minor, then persistent. Eventually the pain becomes strong enough to justify a medical appointment.

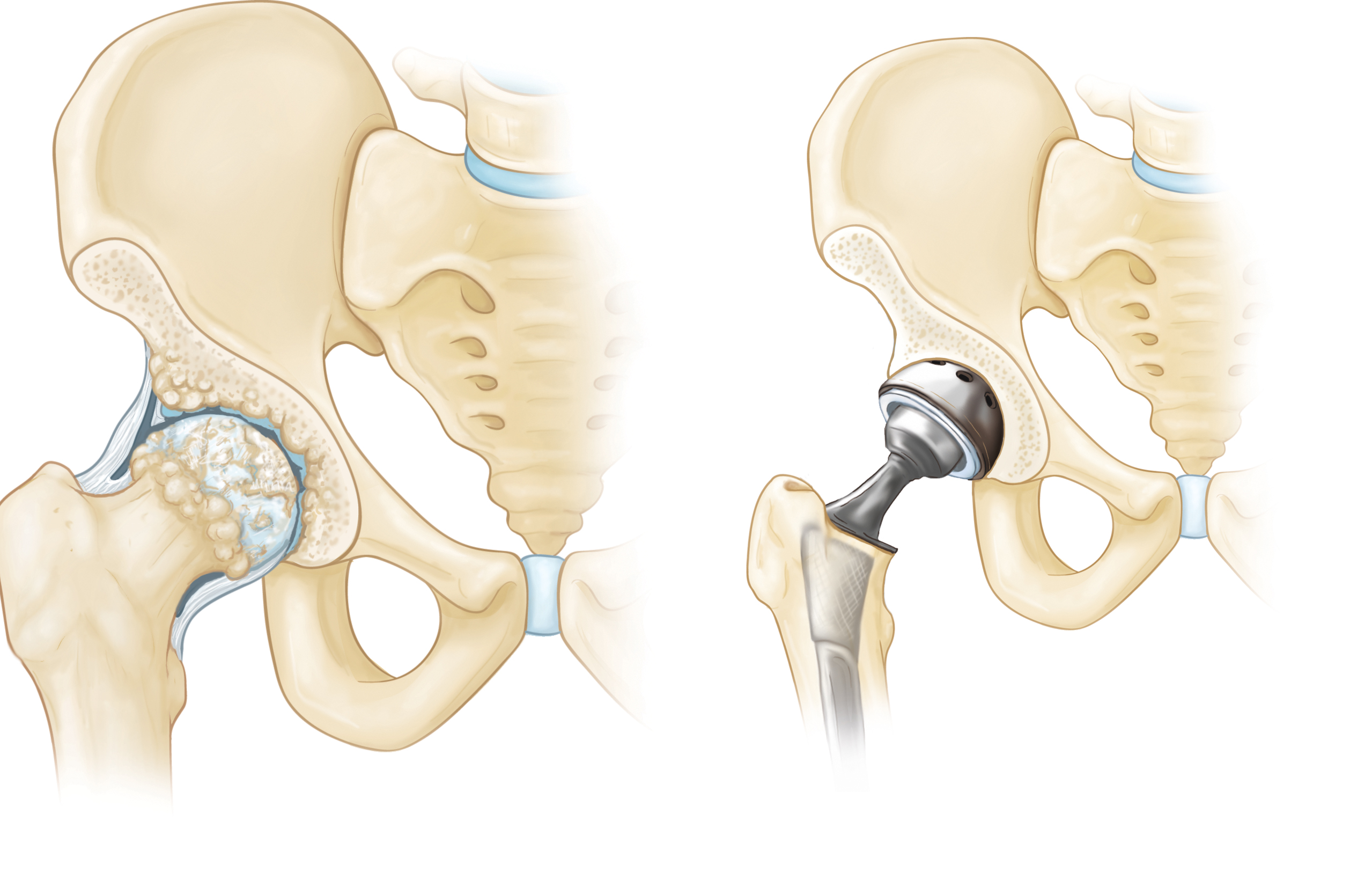

After imaging confirms osteoarthritis, the conversation often follows a predictable structure. Surgery is not necessary yet. Medication may help temporarily. Exercise becomes the central recommendation.

This pattern exists across many healthcare systems because exercise carries clear advantages. It is low cost, widely accessible, and generally safe when done correctly. Moreover, it improves cardiovascular health, balance, and mental wellbeing.

Yet the new analysis suggests that when researchers isolate joint pain and physical function alone, the average improvement is modest.

Not zero. But smaller than many patients imagine.

Looking Across Many Studies Instead of Just One

}

Individual clinical studies can sometimes produce optimistic conclusions. That is normal. Small trials often focus on specific populations or carefully controlled conditions.

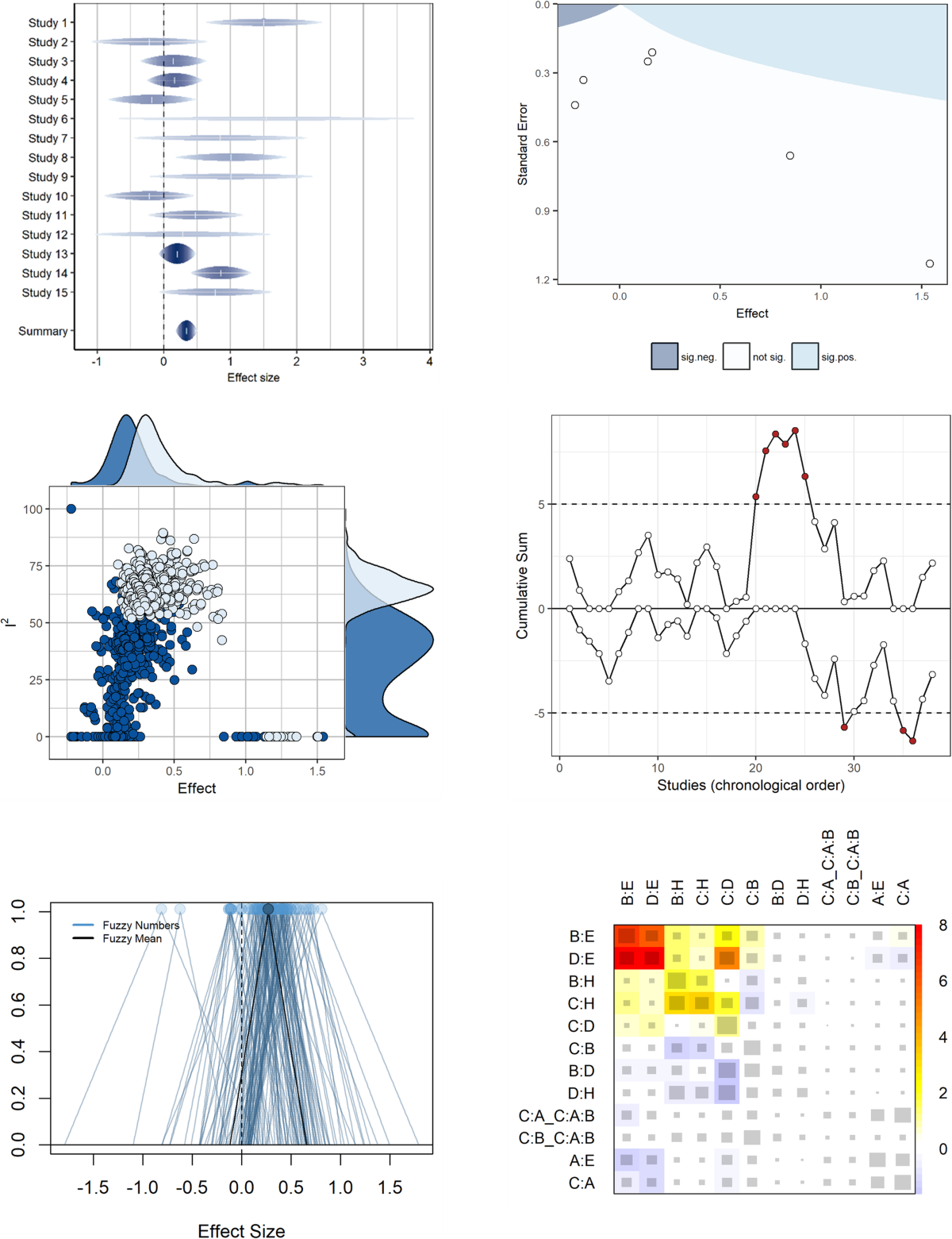

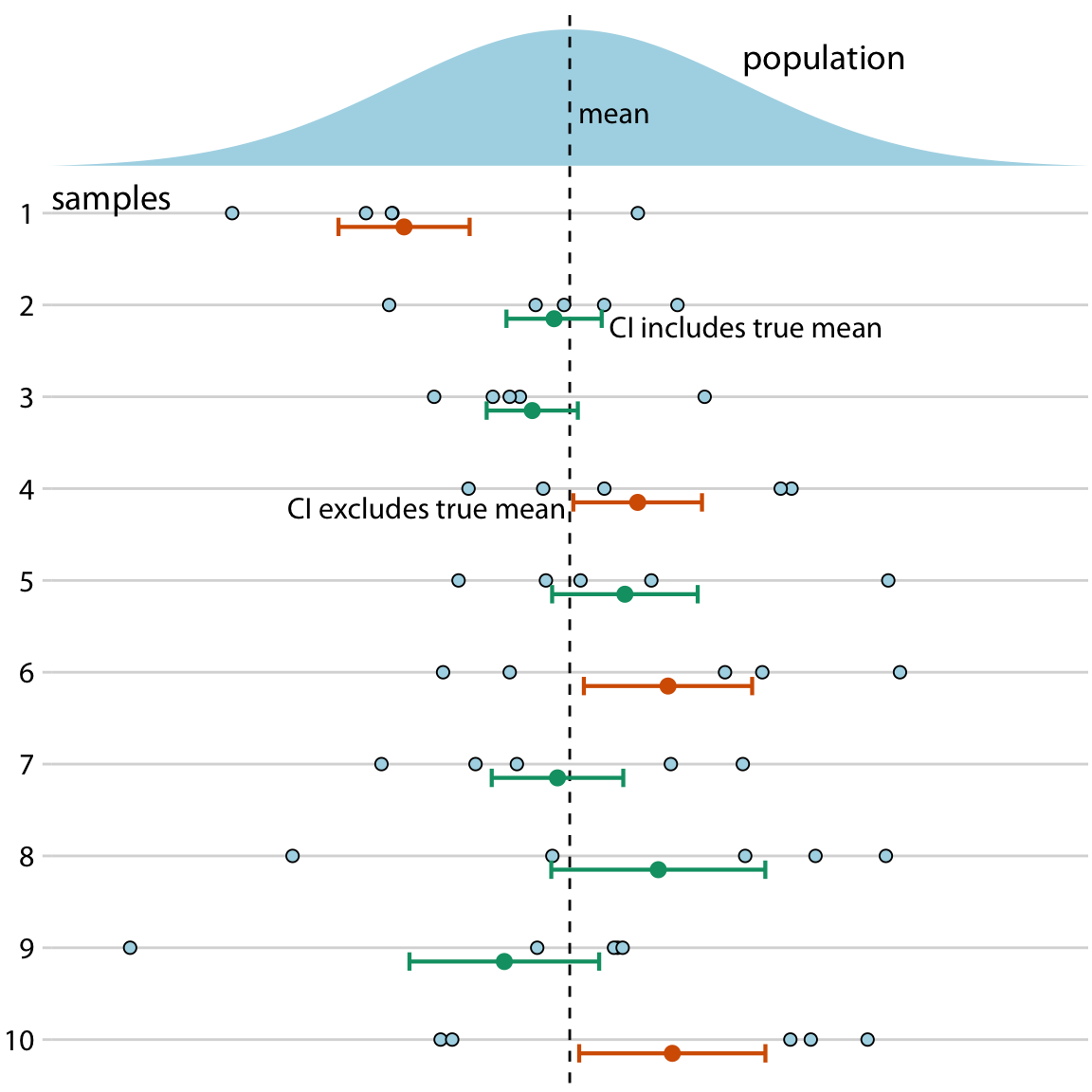

The researchers behind this new work took a broader approach. Instead of relying on one dataset, they conducted what is known as an umbrella review. In simple terms, they analyzed multiple systematic reviews and combined them with additional randomized clinical trials.

The final dataset included thousands of participants across different forms of osteoarthritis involving the knee, hip, hand, and ankle.

This type of large scale synthesis tends to smooth out extreme results. Dramatic improvements seen in small studies often become more moderate when averaged across larger populations.

That is exactly what happened here.

What the Results Actually Suggest

When the data were pooled together, exercise showed small reductions in knee pain compared with placebo or no treatment. The key detail is duration. Improvements often faded over time.

For hip osteoarthritis, the effect was even less noticeable. For hand osteoarthritis, benefits appeared mild.

Interestingly, exercise performed roughly the same as several other treatment approaches including patient education programs, manual therapy techniques, common pain medications, and certain injection treatments.

This does not mean all treatments are identical. Instead, it suggests that many interventions produce similar moderate outcomes rather than dramatic transformations.

That perspective can feel surprising because public health messaging often highlights exercise as a strongly effective first step.

Reality appears more nuanced.

Why Expectations May Be Part of the Problem

There is an interesting psychological dimension here. When patients hear that exercise helps osteoarthritis, they may imagine a clear improvement in daily comfort. Less pain when walking. Easier movement when standing up. Fewer limitations overall.

Sometimes that happens.

Other times, the improvement is subtle. A patient might still feel discomfort but notice slightly better stability or endurance.

In real life, those small gains can be difficult to recognize. Without obvious changes, motivation often declines. Exercise routines become inconsistent. The potential benefit shrinks further.

This creates a feedback loop where expectations and outcomes influence each other.

Therefore, part of the conversation may need to shift from exercise as a cure toward exercise as one piece of a broader strategy.

Differences Between Individuals Matter More Than Expected

}

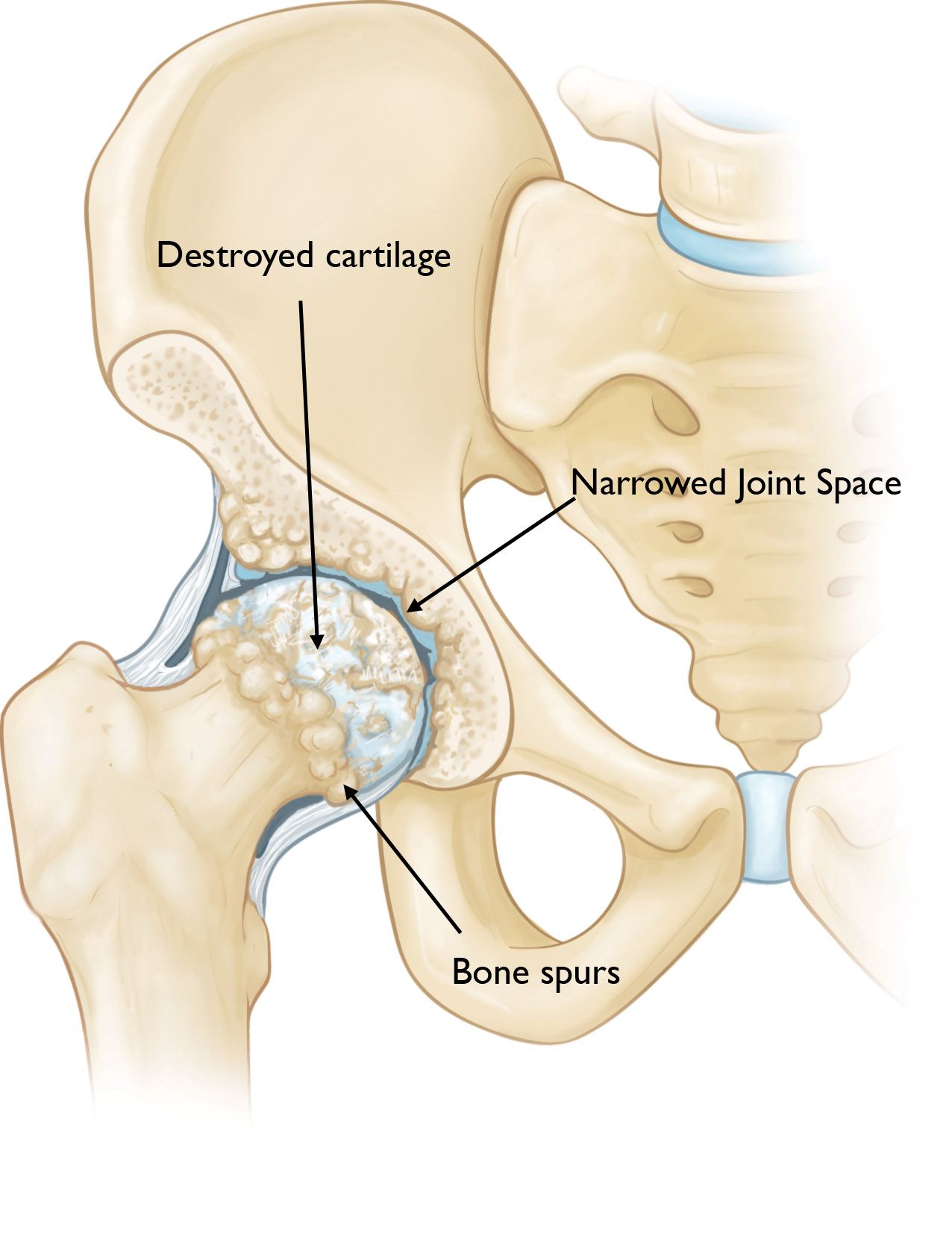

One limitation that appears repeatedly in osteoarthritis research involves patient variability. Not all joint degeneration progresses the same way.

Two individuals with similar imaging results may experience completely different symptom levels. One person might continue hiking comfortably. Another may struggle with daily movement.

Muscle strength, body weight, inflammation levels, previous injuries, and genetic factors all contribute to how osteoarthritis behaves.

Because of this variability, exercise may produce meaningful improvement for some patients while offering minimal change for others.

The new analysis indirectly highlights this reality. Averaged results appear modest, but individual responses still vary widely.

Comparing Exercise With More Invasive Treatments

}

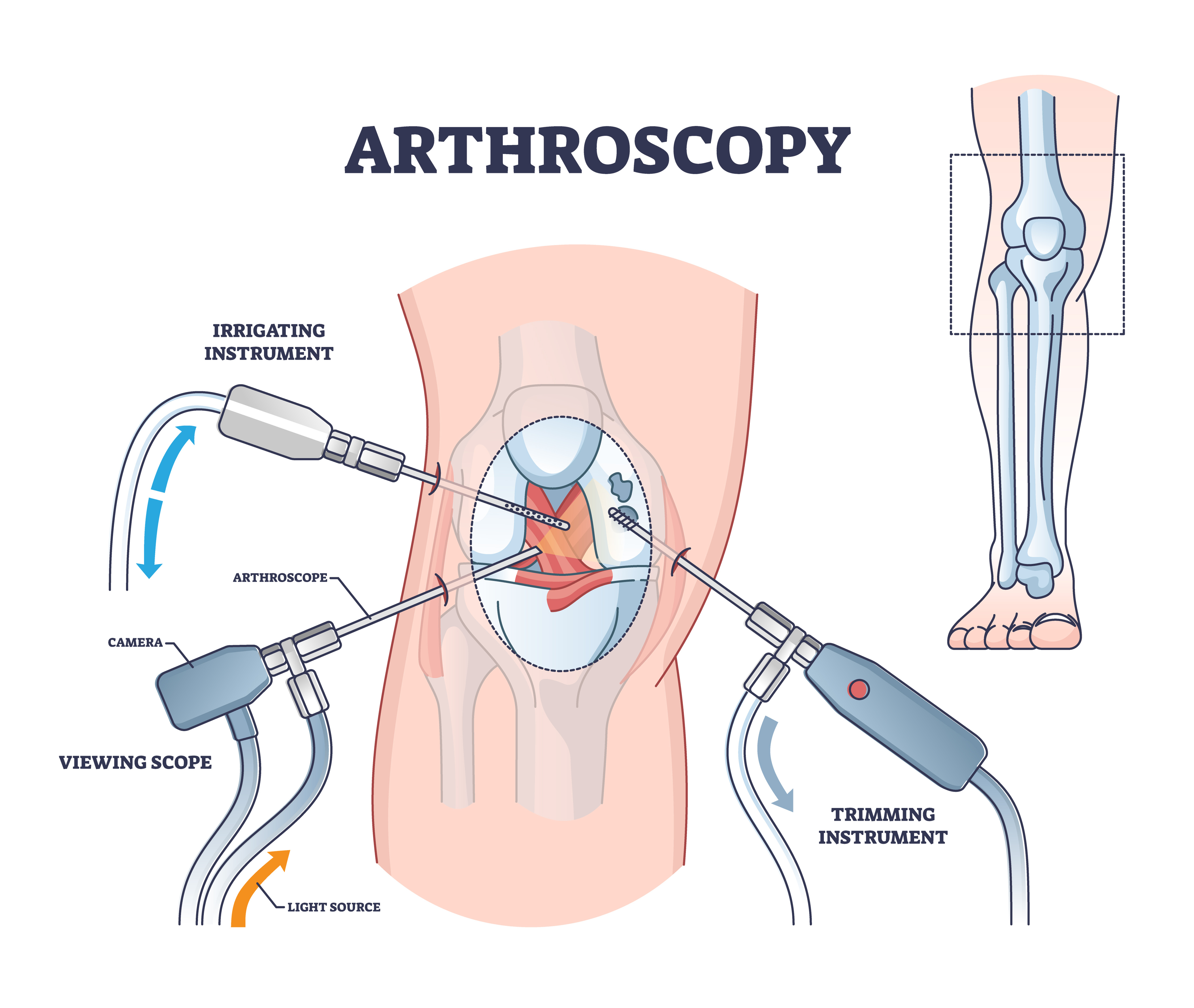

Some trials included comparisons between exercise and surgical interventions such as arthroscopy or joint replacement.

Long term outcomes in those comparisons sometimes favored surgical approaches, particularly in advanced disease stages.

However, interpretation requires caution. Surgery is typically reserved for more severe cases. Patients entering those trials may already differ significantly from those using exercise therapy alone.

Additionally, surgery carries its own risks and recovery timelines.

Therefore, the takeaway is not that exercise should be replaced by surgery, but rather that treatment effectiveness depends heavily on disease stage.

This reinforces the idea that osteoarthritis management cannot rely on a single universal solution.

Understanding the Limits of the Evidence

}

The researchers themselves acknowledge several limitations.

Not all studies directly compared exercise with every alternative treatment. Some allowed participants to use additional therapies simultaneously. Follow up durations varied widely.

Moreover, evidence certainty levels were sometimes low. That does not invalidate the findings, but it reduces confidence in precise effect size estimates.

This kind of uncertainty is common in long term musculoskeletal research. Pain perception, lifestyle behavior, and adherence to exercise routines are difficult to standardize across large populations.

Still, the consistency of modest results across many datasets suggests that expectations should remain realistic.

Exercise Still Offers Important Secondary Benefits

One of the most important clarifications in the research is often overlooked at first glance.

Even if exercise produces limited improvements in joint pain alone, it still contributes to overall health in meaningful ways.

Regular movement supports heart function, metabolic stability, sleep quality, and mental resilience. It also reduces fall risk by improving balance and coordination.

For many older adults, these secondary benefits may be just as valuable as direct joint symptom changes.

In other words, exercise may not dramatically repair cartilage, but it helps maintain functional independence.

That outcome remains extremely important.

A More Personalized Approach May Be the Real Lesson

}

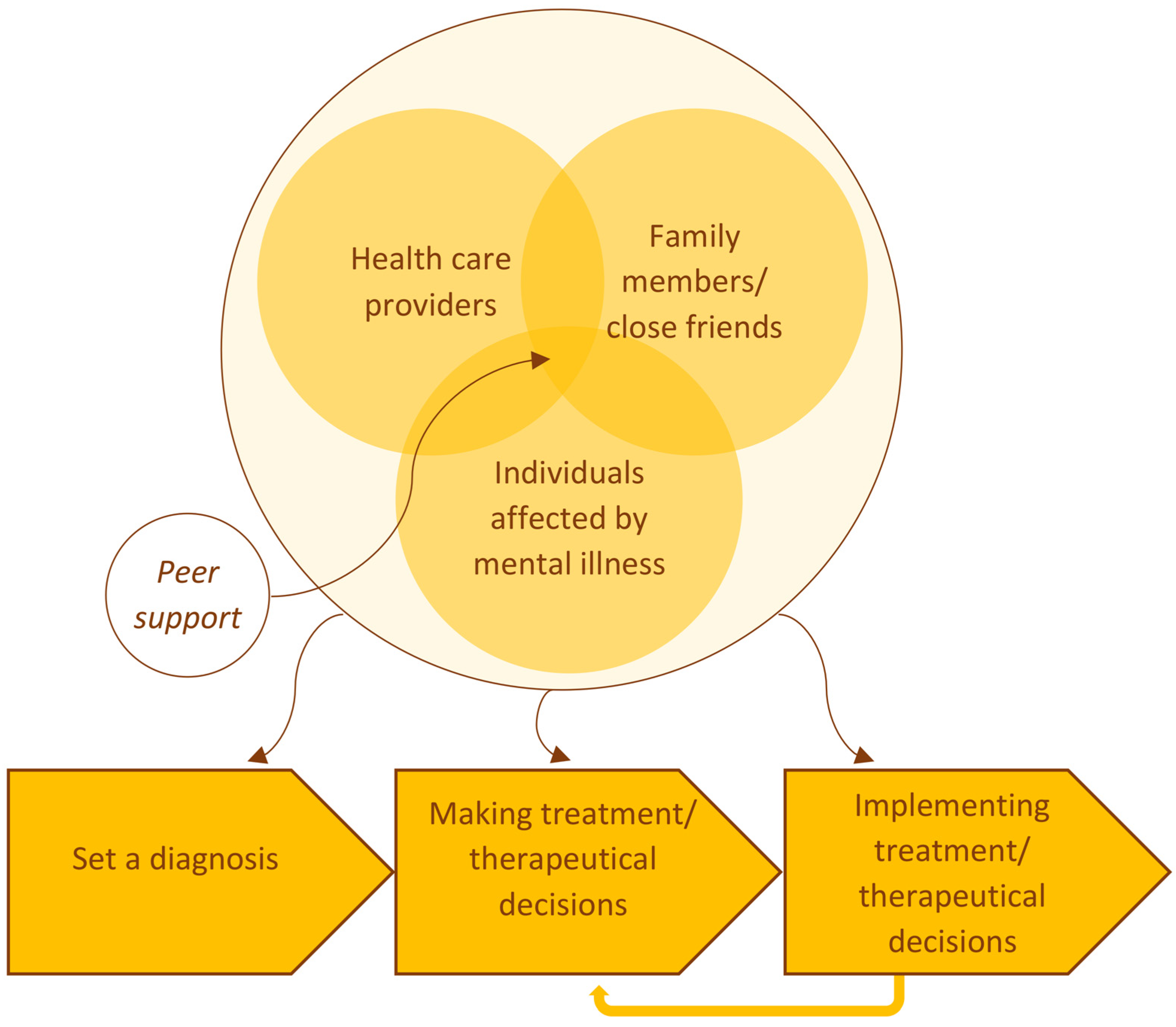

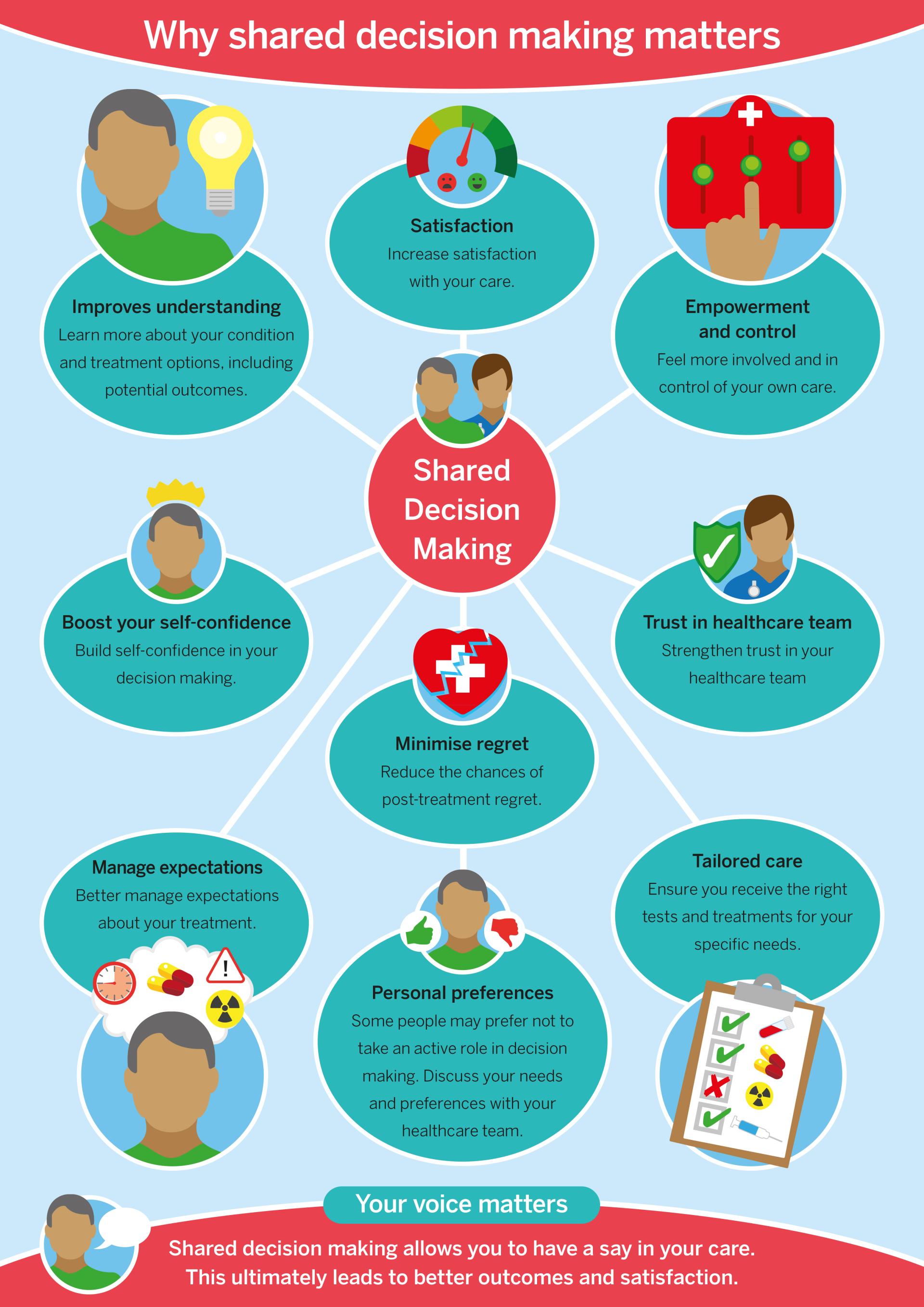

Perhaps the most constructive takeaway from this research is not skepticism but refinement.

Instead of treating exercise as a universal first step for everyone, clinicians may need to tailor strategies more carefully. Some patients respond well to strengthening programs. Others benefit more from weight management, targeted injections, or surgical evaluation.

Shared decision making becomes essential here. Patients bring personal goals, tolerance levels, and lifestyle constraints that influence treatment success.

A person who enjoys swimming may remain consistent with aquatic therapy. Someone else may prefer short walking routines combined with occasional physiotherapy sessions.

Matching treatment style to individual behavior often determines real world outcomes.

Why Medical Advice Evolves Over Time

Medical guidance rarely stays fixed. As datasets expand and analytical tools improve, recommendations gradually adjust.

Osteoarthritis research illustrates this process clearly. Early studies highlighted exercise as broadly effective. Larger reviews now suggest the effect is more moderate.

Neither perspective is entirely wrong. Earlier work identified genuine benefits. Newer research simply clarifies their scale and duration.

This kind of refinement is how medicine progresses.

Rather than replacing one idea with another, knowledge becomes more precise.

Living With Osteoarthritis in the Real World

Outside research environments, osteoarthritis management rarely involves a single solution anyway.

Many people combine strategies without labeling them formally. A knee brace during long walks. Occasional anti inflammatory medication. Gentle strength exercises a few times per week. Adjustments in daily routines such as using handrails or avoiding high impact activity.

These practical adaptations often matter as much as structured therapy programs.

When viewed this way, exercise remains useful, just not magical.

And perhaps that is the most realistic interpretation.

A Balanced Perspective Moving Forward

The new analysis does not suggest abandoning exercise. It suggests reconsidering expectations.

Exercise helps some people more than others. Its effects may fade without consistency. It works best when integrated with other approaches rather than used alone.

For patients, this perspective can actually be reassuring. Limited improvement does not mean failure. It simply reflects the complex nature of joint degeneration.

For clinicians, the findings encourage deeper conversations about personalized care.

And for researchers, the results open new questions about which combinations of therapies produce the strongest long term outcomes.

Osteoarthritis remains one of the most common chronic conditions worldwide. Solutions will likely emerge through gradual optimization rather than dramatic breakthroughs.

In the meantime, movement still matters. Just not always in the way we once assumed.

Open Your Mind !!!

Source: SciTech

Comments

Post a Comment